Sustainable microservices, my opinions and advice

At Echo we mostly wrote services in Go (created by Lile). This semi-opinionated guide seeks to answer some frequently asked questions from engineers new to Echo about (micro)services, Go and distributed systems in general.

This is a guide on how to implement the softer and more difficult concept of “good patterns,” or “best practices.” These things are often discussed in pull-requests or when designing features, and they are generally opinions rather than “right or wrong” situations.

This is not a guide on how to run or operate microservices and as such, this will not cover things like load balancing, monitoring, Kubernetes, etc. But it absolutely should answer questions like “should this be an RPC or a Pub/Sub?”, “is this one or multiple services?” and “does this belong in a transaction?” (yes, always yes).

Protobuf first, code later

When thinking about a new service or even just an RPC, we start with the proto file. We love proto, it’s a useful technique for seeing if the models and API make sense, if you’re missing things, and for getting feedback. Our services often start as a pull request with just one file!

syntax = "proto3";

package orders;

option go_package = "github.com/echo-health/orders";

import "google/protobuf/timestamp.proto";

enum OrderStatus {

STATUS_UNKNOWN = 0;

STATUS_NEW = 1;

STATUS_PICKING = 7;

STATUS_DISPATCHING = 9;

STATUS_DISPATCHED = 10;

STATUS_CANCELLED = 11;

}

message Order {

string id = 1;

string medication_id = 2; // VMP or AMP

google.protobuf.Timestamp create_time = 3;

google.protobuf.Timestamp update_time = 4;

}

message GetRequest {

string repeated ids = 1;

}

message GetResponse {

repeated Order order = 1;

}

service Orders {

rpc Get(GetRequest) returns (GetResponse);

}

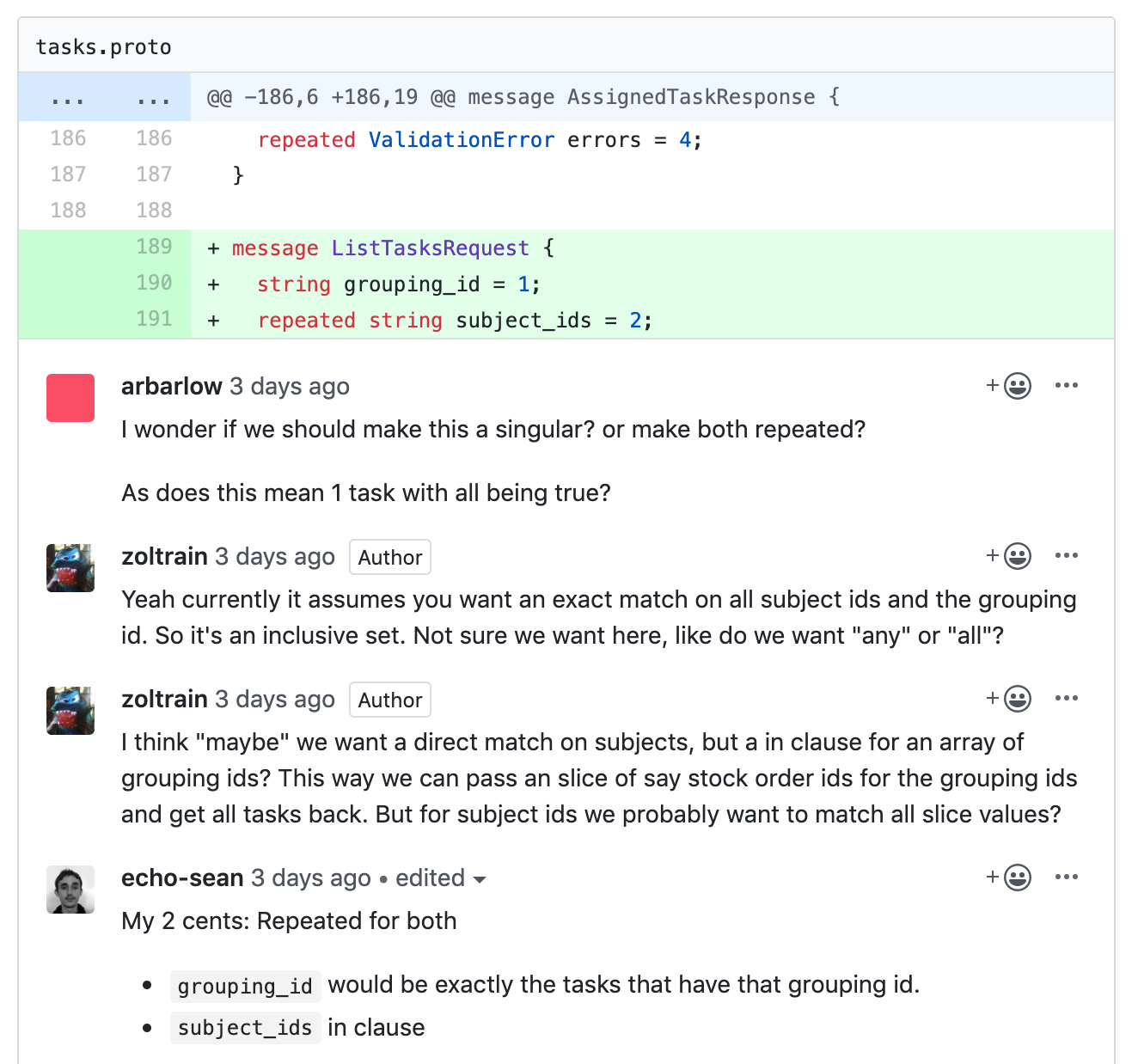

We often have pull request conversations around a proto like below, which we can resolve before anyone writes any code.

Don’t cross models (protobuf models)

This one is one of our few hard rules - do not import other service’s type definitions into your service’s proto file. For example, given an accounts service and an orders service, you don’t want to do this:

syntax = "proto3";

package orders;

option go_package = "github.com/echo-health/orders";

import "google/protobuf/timestamp.proto";

import "yourcompany/accounts.proto";

message Order {

string id = 1;

string medication_id = 2; // VMP or AMP

accounts.Account account = 3; // <-- DON'T DO THIS!

google.protobuf.Timestamp create_time = 4;

google.protobuf.Timestamp update_time = 5;

}

It’s hard to compile for a start, but also means that changes to the accounts API, won’t be reflected in this proto, causing confusion with types, coupling, importing in other code and similar issues. It also means you’ll have to fetch the whole account every time. It’s just full of problems and should be completely avoided. Instead, store the account_id or similar and let the system in question fetch it if need be.

syntax = "proto3";

package orders;

option go_package = "github.com/echo-health/orders";

import "google/protobuf/timestamp.proto";

import "echo-health/accounts.proto";

message Order {

string id = 1;

string medication_id = 2; // VMP or AMP

string account_id = 3;

google.protobuf.Timestamp create_time = 4;

google.protobuf.Timestamp update_time = 5;

}

Ssssh, tables are a secret

On the topic of proto files and services, it’s important to keep your external representations of objects and models different to the internal versions of your service. Whilst it may seem easy to simple copy proto objects straight to a database and vice versa, this is leaking implementation and will make it very difficult to refactor under the hood if you decided to change your database or something similar. It also allows you to add “computed” fields, which can simply be useful to the user of the API.

For example, our proto objects often have embedded objects that don’t always reflect our database schema.

message Order {

string id = 1;

string medication_id = 2;

repeated Dispatch dispatches = 3;

OrderStatus status = 4;

google.protobuf.Timestamp create_time = 5;

google.protobuf.Timestamp update_time = 6;

}

message Dispatch {

string id = 1;

google.protobuf.Timestamp create_time = 2;

google.protobuf.Timestamp update_time = 3;

}

In the example above, it may appear that an order can have many dispatches but that a dispatch is linked to a single order. In reality this is a many-to-many relationship with a join table, but to prevent a cyclic loop and also to simplify the returned model we don't include an order field in the Dispatch message.

Transactions are your friend

This isn’t (micro)service specific, but if your database supports them then transactions definitely are your friend.

For example, a common pattern is to do some SQL, then call an API or vice versa. However this can lead to a broken state of affairs.

Consider this RPC to refund and order via Stripe that we’re storing in our database.

o, err := db.GetOrder(ctx, orderId)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.InvalidArgument,

"couldn't find order (%s): %s", orderId, err)

}

err := stripe.RefundCharge(ctx, o.ChargeID)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

err := db.Refund(ctx, orderId)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.Internal,

"couldn't refund order: %s", err)

}

return &orders.RefundResponse{Id: orderId}, nil

This is bad, as whilst we are protected from Stripe failures, meaning we wouldn’t create a refund in our database if Stripe doesn’t work, we are susceptible to issues if our database insert fails due to validation or database constraints. If the user then tapped again, they could be refunded twice. Or if we were charging them money, we could charge them twice!

Instead, let’s use a function that can wrap our code in a transaction, calling BEGIN and COMMIT for us.

err := WrapTransaction(ctx, db, func(ctx context.Context, tx *gorm.DB) error {

o, err := tx.GetOrder(ctx, orderId, db.WithUpdate(true))

if err != nil {

return err

}

err := tx.Refund(ctx, orderId)

if err != nil && err == db.OrderAlreadyRefunded {

return nil

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

return stripe.RefundCharge(ctx, o.ChargeID)

})

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &orders.RefundResponse{Id: orderId}, nil

Whilst not perfect, we are now safe from an INSERT going wrong, as we won’t refund until we have a good INSERT and if the refund fails, we’ll roll the whole thing back.

Note also that here we can also avoid duplicates and race conditions, as our Get of the order includes FOR UPDATE which will lock that row from any updates until we’re finished. We’re also checking here after we get the order to see if it’s already refunded and we’re performing a no-op. You should definitely write a test for this!

You may need to store the result from another service in the database as well — in that case I recommend doing to the smallest update possible, as this should have a smaller chance of failure. However, you should still write tests!

UPDATE orders SET refund_id = 'rfd_001' where id = 'ord_0001';

If you need to wait, use RPC, everything else is Pub/Sub

A general rule of thumb is that if you need a result straight away, use a remote procedure call (RPC), and if you don’t, trigger a Pub/Sub.

For example, most RPCs don’t wait for emails to send or our analytics store to update. That is done via Pub/Sub, as we want those things to happen but we don’t want to wait for them to happen.

It’s good practice to limit writes to the service that’s doing the RPC, and let writes to other services/systems happen over Pub/Sub. This makes it easier to code around failures and transaction issues.

Use Pub/Sub when it must happen

Further to the above, RPCs can fail, informing the user of a failure. Allowing them to decide to retry or not (i.e. needing to add more information). But this is often undesirable behaviour in a distributed system, when work is being done in the background.

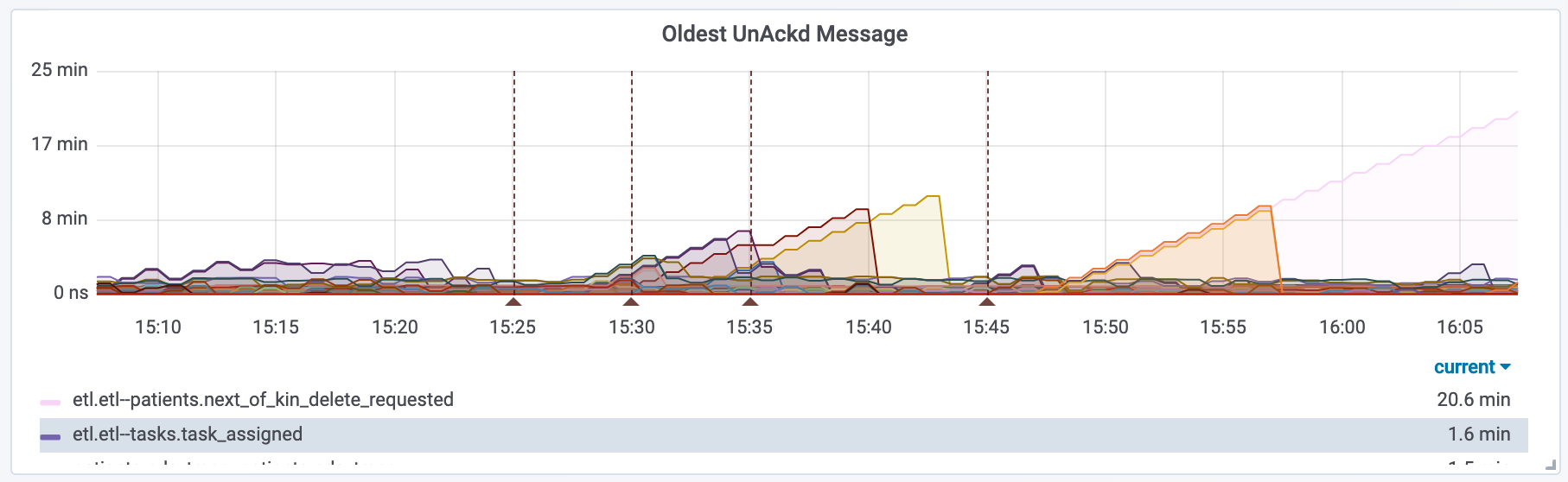

For example, imagine if you run a cronjob to alert people of an expired credit card. If you ran a for loop with an RPC to email them, and that RPC has problems, no-one would be notified even after the issue with the email system has been resolved. With Pub/Sub the queue will build up, but once the problem has been solved the queue will drain. Emails are important, but this also applies to audit logs or any other important task. Queues can be monitored, alarms triggered when messages are old or unprocessed, and then the underlying issue can be fixed.

This also protects you from external systems and services. For example, our audit logs are stored in BigQuery and this happens via a Pub/Sub with every mutating action. If BigQuery is down it won’t affect any of our services, and when BigQuery comes back the records will be written just fine.

Keep databases separate

Our services never share a database with other services. In our case, they don’t even share the same instance or machine, database-wise.

This has benefits from a security perspective for sure, but also guarantees isolation of databases and any issues around upgrading, disk space, failover over etc. You could also achieve a similar situation by using a clustered database like CockroachDB or Google Spanner.

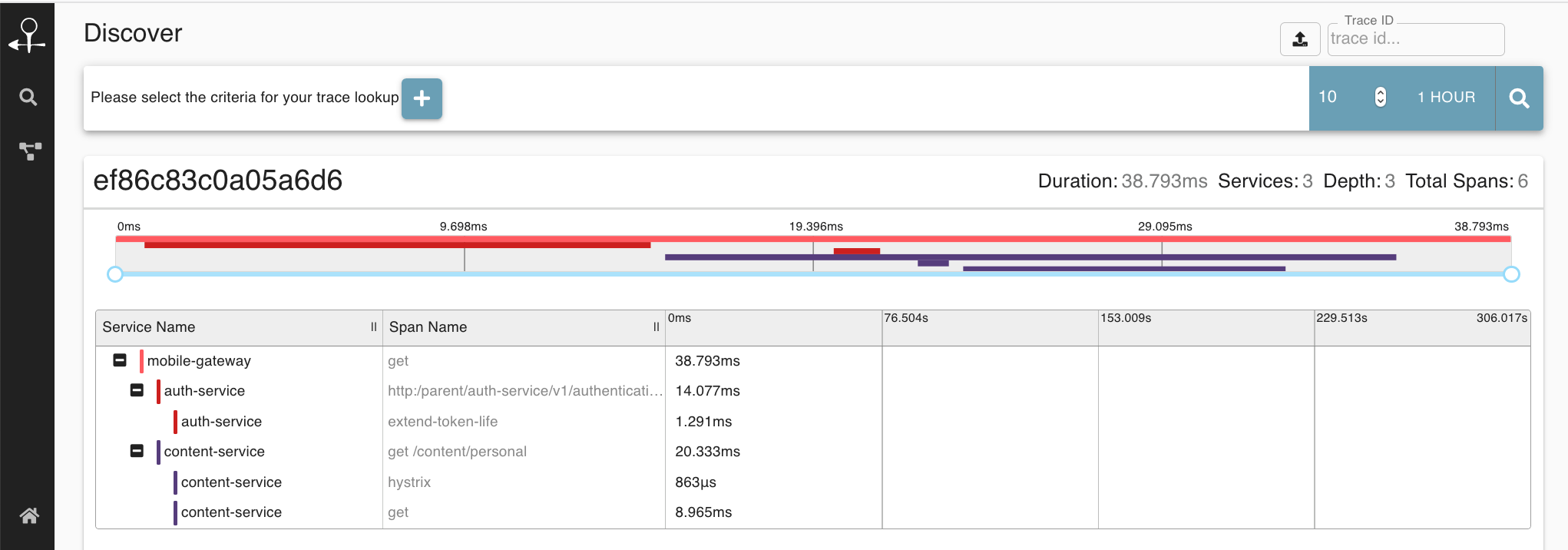

Don’t log, trace

Whilst simple logging can be useful in some circumstances, in general, it’s much better to annotate a trace. If you do log, log to the trace and STDOUT if possible, this means in the log file you’ll have a trace ID and can jump straight to the trace, which will show that log line in context of the whole system. We use Logr for this purpose.

Idempotency is important

An important outcome of the section “Transactions are your friend” was the effect that by implementing a simple transaction, we avoided duplicate refunds or charges when the same RPC was called twice in quick succession. This is super important in RPCs but even more important when subscribing to Pub/Subs. There is no guarantee that a message will be received only once and it may be twice at the same time or a couple of times over an hour, depending on your configuration. It’s important that if the subscriber fails, it fails cleanly and, hopefully, does nothing but fail.

Distributed transactions are hard, so avoid them

Much has been written online about microservices and the absolute requirement to do distributed transactions. They are however incredibly hard to implement and often can be solved by simply designing or architecting the code a little differently.

You can often achieve the same level of atomicity by only performing writes in the service performing the RPC itself, and then using Pub/Sub to persist other actions.

It’s our belief that distributed transactions come with a high complexity tax, they’re hard to test, and they’re very hard to get right. This is why we think they should be avoided wherever possible. We think the time is better used searching for an alternate design that removes the need to use one in the first place.

Keep server, subscriber and model layers separate.

This keeps things testable, simpler and easier to both refactor and re-use. It’s recommended that you do as little as possible in your server/requests or subscribers and simply call functions in the model layer or a package to do complex actions.

For example, imagine you wanted to work out what to pick in a warehouse by checking stock, selecting the right packets and then decrementing the stock level. The functionality for this should be moved into a package or database layer, so that both a server and subscriber can call the same logic.

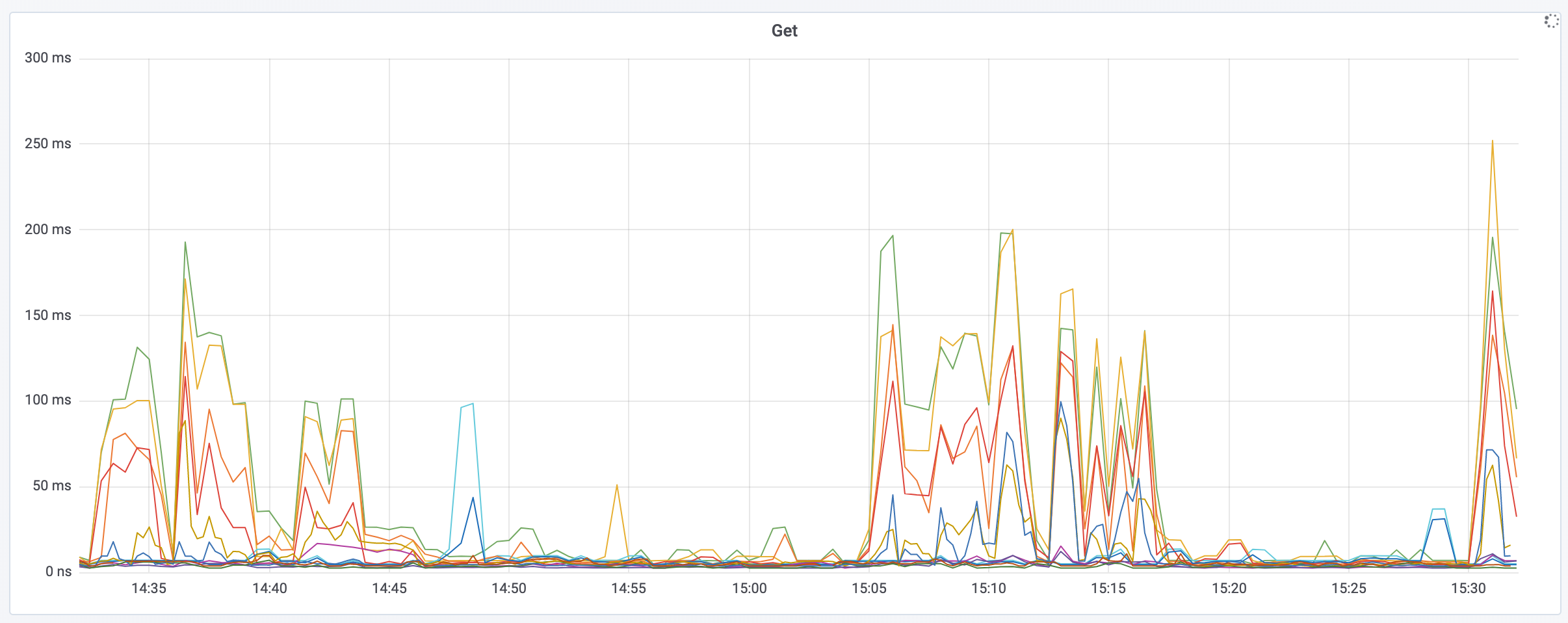

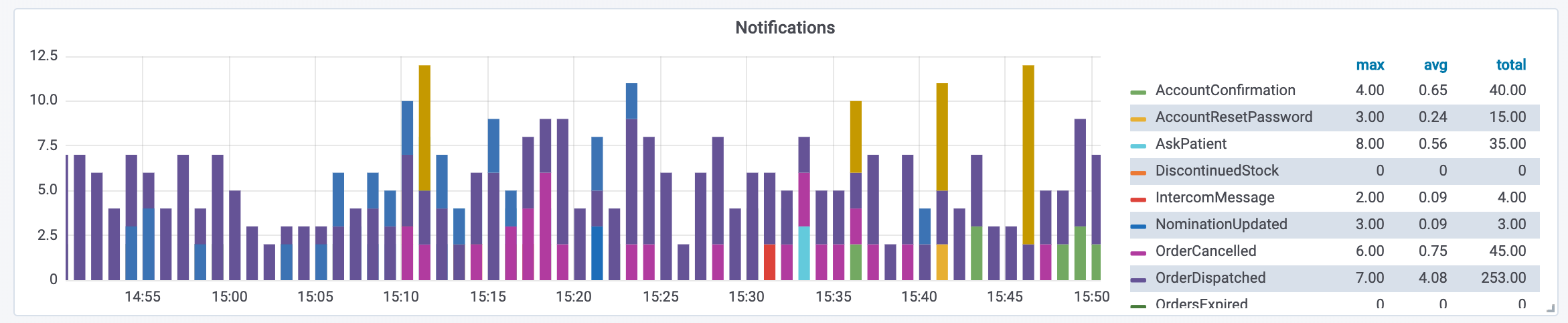

Graphs are good

Graphs are super important in order to know how a deploy is going and how your service is behaving on a low level.

But you can also instrument things like “emails sent” or other useful and interesting things, which may or may not belong in analytics.

This is a breakdown of notification types from our notifications service. Monitoring graphs like this regularly can help you identify issues with a specific service.

Write code that can always be shipped, even if by mistake

This can definitely require more engineering effort, but in general you should always try to write code that is forwards/backwards compatible, allowing you to deploy at any time, even during peak hours without affecting clients that already use your service. This generally means doing things like:

- Adding fields instead of removing or re-naming.

- Not removing a field right away if it’s not being used anymore. Mark it deprecated and have a timeline to completely remove it.

- Not changing the numbered tags for the fields in the messages.

- Re-computing the value of the old field, if it’s no longer in the database or similar, so old clients aren’t effected.

- If you are changing an RPC significantly, just create a new one.

- Gating things behind environment variables or settings if they have an immediate impact upon being set.

That’s it! As noted above, this is more of a guide than a list of requirements. Let us know if you have any comments or feedback!